The Spanish Affairs

The Spanish Affair was a name given to two unrelated incidents which would have unforeseen impact on the Savoyard society and its politics.

The first of these was a scandal regarding king Charles Albert's son Vittorio Emmanuele and a daughter of Spanish marquis of Algecilla, Agata. The family had sought refuge from Sardinia-Piedmont due to the ongoing civil war in Spain.

Agata had apparently become pregnant during their stay at Turin and the family was forced to continue to France out of embarrassment. Rumours of a local servant being the father spread like wildfire, until they took a more radical turn due to a British newspaper The Manchester Guardian which had taken interest in the story.

The paper made a bold claim that the father was actually Prince Vittorio Emmanuele instead of a Piedmontese commoner. The whole kingdom was shocked by this and out of fear that further scandals would ruin the royal house's reputation, the government decided to enact a radical law prohibiting importation and distribution of foreign newspapers in the kingdom. The new decree literally angered the nobility.

Young Vittorio Emmanuele, future king of Italy.

Although printing of newspapers was already forbidden in Sardinia-Piedmont, there were no laws regarding foreign publications which were popular among the more literal subjects. Plenty of small, local papers were printed all over the kingdom which operated underground or with quiet acceptance from local officials. But after the outrage followed by the new ban set on foreign gazettes, their volumes exploded. Funded by liberal aristocrats and distributed in secret they amassed huge popularity although none would gain stature as a national news outlet yet. Still, these papers would act as important messengers for liberal ideas in the kingdom.

This incident radically changed the atmosphere in Sardinia-Piedmont regarding freedom of information and press rights with large proportion of the upper classes demanding for an independent newspaper.

Even though it is now known that it wasn't Charles Albert's son who had impregnated Agata, the rumours were never denied by the royal house who believed such would have meant giving in to the power of the media, instead trusting the old saying: out of sight out of mind. Vittorio Emmanuel was soon after sent to study in Paris.

The second affair was the question regarding the Carlist Wars of Spain, fought between two claimants to the Spanish throne – the pretender Carlos V and Isabella II, whose mother was acting as a regent for the infant-queen.

Although the Carlists were pushing for reinstitution of an absolute monarchy similar to that of Sardinia, supporting the pretenders was out of question with major powers such as France and UK lending hand to the liberal Isabelinos. Yet, the war was very much undecided; Don Carlos, as the pretender king was called, was enjoying strong support in Catalonia and the Basque country and people in the rural areas tended to be sympathetic to his cause.

Carlist victory would have indeed been the favourable option for Sardinia-Piedmont, but the official stand remained neutral. However, hundreds of volunteers set sail to Spain and joined the struggle on the Carlist side. This worried the largely liberal nobility on the island of Sardinia who were seeking further autonomy and moderate reforms similar to those supported by the Spanish queen regent Maria Christina.

To counter the influx of young, adventurous men filling up the Carlist ranks, a decision was made by the liberal Cagliari Society to send their own expedition to Spain. Their idea soon gained popular support on the relatively progressive island and men flocked to their ranks in such numbers it even alerted the islands officials. Support for the liberal cause was worrisome to many; if the reformists could gather an army of men to fight for their cause abroad, there was a risk they might gain the courage to try forcing their demands at home too. The risk was so high that local military officers sent an official petition to the king requesting for authorisation to use force at disbanding the volunteers and the whole society.

Although Charles Albert and his ministers were at least as concerned as the Sardinian officials, there was little they could do. Sardinian people were reluctant to obey Piedmontese rule and disbanding the Cagliari Society, popular amongst the upper classes, was out of question. The club had a relatively large influence over the kingdom's administration. Many of the members came from a younger generation of old and powerful families – there were even members from the House of Savoy itself involved, none as much as Girolamo di Savoia.

Like the king himself, Girolamo di Savoia had studied first in Genoa and later on in Paris and had been swallowed into liberal circles early on. Now back in his homeland, the 26 years old captain of the Carabinieri was one of the Cagliari Society's founding members and an important ally for the liberals due to his influence; his father, Amadeo di Savoia, was head of the ministry of trade and shipping – a powerful political body in control of the kingdom's tolls and tariffs.

The only preserved picture of Girolamo di Savoia, mid-19th century.

His relations within the government were crucial for the expedition's survival; he managed to strike a deal with the king, according to which he would immediately leave the island with his current volunteers and resign as an officer in order to avoid a possible scandal. Slightly more than thousand volunteers packed their belongings and sailed to the Spanish island of Mallorca where Girolamo would continue his recruitment.

The liberal army, known as the

Italian Brigade, consisted of mainly Sardinians, but men from all over Italy flocked to their ranks. Recruits found their way to Mallorca especially from the Austrian controlled Venetia and Lombardy, areas eager to regain their independence. In total the army managed to raise as many as 5000 volunteers to help the Spanish crown.

In late August 1836 Girolamo di Savoia decided it was time to make a landing on the mainland in Castellon, a former Carlist region now controlled by the government. The Spanish command gave urgent orders to the Italian Brigade upon their arrival; they were to head to Teruel where the Carlist army was assembling, preparing for a march to Madrid. Girolamo and his men would take part in the decisive battle there.

The Italian commander started his advance towards the Carlist main army on 1st of September 1836 as was requested by the Spaniards. The two armies were to arrive on the same day to face the rebels together and surround their poorly prepared troops, but the plan was doomed to fail.

Torrential rains had brought the Spanish army to a halt for many days as their artillery was constantly stuck in deep mud, considerably slowing down their marching speed. Girolamo couldn't have possibly known of this unfortunate setback and no messenger would bring a word to him in time.

The rebels had set their base in a small town of Alfambra, less than 30 kilometres north of the city of Teruel. The Italian Brigade arrived to the town's outskirts at night between 1st and 2nd of September. There was a tiny river not much larger than a ditch between the Italians and Alfambra, which lied on a hillside. With the misconception that there would be Spanish troops nearby, Girolamo gave orders to open fire against the village with six cannons donated by the Spaniards.

The far superior Carlist army was taken by surprise and initially thought this was a major offence concluded by the Spanish army; the bombardment ravaged the town's fairly frail buildings and caused minor casualties to the Carlist forces. The rebels quickly organised their troops to face the Italian attack and opened fire to the enemy across the river, although they didn't have a clear image where Girolamo's men were positioned.

The Carlist army consisted of nearly 24 000 men compared to Girolamo's 5000 Italians volunteers and was armed with seven mortars and 12 smaller field guns. The exchange of fire lasted for nearly two hours but caused little casualties on either side apart from the initial Italian opening.

When the Carlist commander, General Agustín Acuña, realised they were at standstill and the liberal army wasn't going to assault their positions, he ordered his men to a full offence against the Italians.

Upon seeing the thousands of rebels crossing the Alfambra river, Girolamo realised they were in this battle alone and the Carlists were concentrating their full force on the handful of Italians. He decided to sound a retreat. General Acuña was surprised by the move and sent his entire army after them.

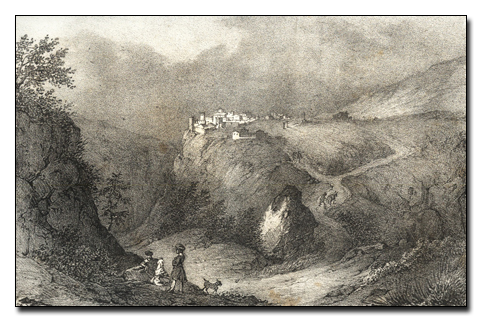

The Italian Brigade wouldn't stop until they had arrived to a town called Cantavieja, situated 55 kilometres east of Alfambra. It was surrounded by steep cliffs and provided excellent protection for its defenders. Girolamo decided to take shelter from the town's old fortifications and mansions situated at the heart of the town, but he knew they didn't have time to properly set up their positions and would be vulnerable for artillery fire.

Early 19th century drawing of Cantavieja.

Cantavieja was a true death-trap; although easily defended, there was only one proper way in and out of the city. Had the Carlists launched an assault against the Italians, the battle would have been short and bitter, but General Acuña was still under the impression he was fighting the main army of the Isabelinos – or at least a large portion of it, and decided it was best not to risk it all in an open offence and instead besieged the Italians, bombarding the town from afar.

Girolamo and his men couldn't properly position or direct their poor-quality cannons and had to take shelter instead of responding to the fire. The situation would last for the following day and night until the Spanish army finally arrived to the scene early in the morning of 4th of September.

The area around Cantavieja is very mountainous and as the liberal army arrived to the Carlists from south-east, they stood on a hill top and would have an advantage due to elevation. The sudden arrival of the Isabelinos caught General Acuña by surprise and to his horror he realised it wasn't the Spanish army trapped in Cantavieja, but a much weaker force.

The liberal army was only four kilometres from the Carlists as the two armies sighted each other and trees and cover were scarce between them. What followed was rather chaotic; the Spanish general sent his thousands of cavalrymen charging down at the rebels, turning them into easy targets on the steep and bare cliffs which prevented full gallop.

General Acuña on the other hand decided it was time to launch a proper offensive against the Italians and nearly 8600 Carlists started assaulting Cantavieja while their comrades were desperately trying to form a defensive column against the liberals.

What followed was a bloodbath both in the town and on the hillside. Girolamo had set up barricades on two of the main streets leading to the town's interior with men positioned on either side and had blocked access to the many alleys – the plan would prove to be a grave mistake.

Upon arrival the rebel forces immediately headed to the large church at the heart of Cantavieja, believing it acted as headquarters for the Italians, although this was actually situated in an old mansion further inside the town. The Carlist forces didn't split along the two available and unblocked routes as had been thought by Girolamo, instead marching through the main street straight into first of the Italians' barricades – chaos erupted. The Carlists, who were packed tight on the narrow street, couldn't respond to fire with their weapons and thus chose to rely on their bayonets.

Without an alternative option they charged against the barricade and into the houses and fought face-to-face with their enemies. Fierce battle ensued as the two sides stabbed, slashed and hacked each other with whatever sharp they could equip themselves with. Shooting was scarce as the men were close enough to feel the warmth of each others.

Drawing of carlist troops.

Both sides suffered grave casualties but the rebels couldn't brake the defenders' positions. Nearly half of the Carlist rebels had been killed or wounded as they tried to retreat back to their main forces. The Italians' situation wasn't any better; with over 3000 casualties they could be considered defeated in that battle.

Meanwhile General Acuño's army had been destroyed by the Queen's forces. The Carlists had had to surrender after a short but bloody struggle in which the liberals had constantly held the upper hand, although all of the cavalry had been sent charging to their own death.

This was the decisive battle that brought an end to the Carlist wars, although smaller skirmishes would continue for years to come and the struggle to regain areas loyal to Don Carlos continued. The pretender king fled to Austria where he passed away in 1848.

The Italian Regiment had suffered greatly and the men had lost most of their enthusiasm. Yet, they were assigned one more task to retake control in the Carlist city of Girona near the French border where they would face no armed resistance.

Girolamo would stay in Spain for the following eight months, even though the Italian regiment was officially disbanded only weeks after raising Piedmontese and Spanish flags in Girona. He enjoyed the victorious and liberal atmosphere of Madrid and was discouraged by the events at Cantavieja. Even though the Italian liberals had suffered a setback that day, they were far from withered away.